What about the Shark?

Why is the story of the USS Shark so important to the communities of Arch Cape and Cannon Beach?

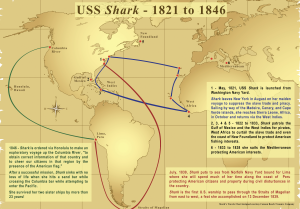

The USS Shark was an 86-foot long schooner with a depth of just 10 feet 3 inches. She was designed to navigate the shallow waters of the West Indies. Constructed in 1821, she was built for speed and maneuverability. During the Shark’s illustrious career she was used to suppress piracy and slave trading throughout the West Indies and off the shores of Africa. She even protected American trade ships in the Mediterranean. In 1831, naturalist James Audubon traveled on the Shark from Florida to New Orleans collect and research specimens. The Shark was also the first U.S. war ship to pass through the Straights of Magellan from East to West in 1833 en route to Peru.

The Secretary of the Navy had this to say of the Shark, “all who witnessed the operations of the Shark were inspired with increased respect for the American Flag.”

President James Polk was elected in 1844 with a large portion of his campaign dedicated to the concept of Manifest Destiny. Manifest Destiny was an idea first written about in the 1820’s by a New York journalist, “It was the nation’s manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.”

Almost immediately after Polk’s election the Shark was sent to join the Pacific Squadron. Polk had to know the disposition of the people living out in the Oregon territory, so the Shark was dispatched to discover the loyalties of those in the region. Under command of a young, but knowledgeable captain, Lt. Howison, the Shark arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River in August of 1846. Unbeknownst to Lt. Howison and the residents of Oregon, the U.S. Senate had already ratified a treaty with Britain on June 15, 1846, that established the international boundary at the 49th parallel, thus making the perilous journey of the Sharkunnecessary.

The Shark stopped off in Astoria, where some of the crew deserted. The shark traveled up the Columbia River to Fort Vancouver and then made their way back down the Columbia by the beginning of September. The Columbia River Bar Pilots were established in 1846, but none were available on the day that Howison wished to attempt the crossing of the great Columbia River Bar. In his own letters Howison sited, “impatience” and “naivety” for him impetuousness.

Whether it be a lack of accurate chart maps, the lack of a bar pilot, a sparse crew, or just the weather September 10, 1846 did not belong to the Shark. Thanks to competing winds and a strong current the ship was pushed onto the dangerous south breakers, Howison attempted to turn north and away, but the raging current had other ideas. The bow was turned directly towards the breakers. Howison dropped anchor, but the chain snapped, and the ship raced into Clatsop Spit (today’s Fort Stevens State Park), where it stuck. Waves began crashing over its side, thus dooming the Shark to a watery grave. The crew of the Shark survived.

In a letter from Howison to Oregon’s provincial governor George Abernathy, Howison laments the loss of the Shark, “You have doubtless heard of the fate of the hapless Shark” “Swept to destruction by the overwhelming strength of the tide, for want of thorough acquaintance with which I did not make due allowance.”

The crew of the Shark took cover in a small fisherman’s shanty, which was supposedly construction by the Corps of Discovery, before they were rescued.

Burr Osborn, crewmember of the Shark said this of the shanty, “We learned… that it had been built by some of Lewis & Clark’s men, some fort years previous.”

After the crew’s rescue, the first concern was for the guns. It is unclear what kind of armament the Shark had when she was lost, but at her last recording it was said that she had two long 9-pounders, eight 24-pound carronades and possibly even a 32-pound carronade. It was a common practice when one ship took another to trade out weaponry and the Shark took many a ship. Because of this, there isn’t a clear record of how many were actually aboard.

However, we do know today that the Shark was home to, at least, three 18-pound carronades. Carronade, you might ask. Carronades were distinguishable by their short size and relative lightweight. Carronade were mounted on a base and held with a large bold that could be adjusted to allow for perfect aim. These shorter carronades (cannons) may appear less menacing than their larger counterparts, but were actually quite dangerous. Carronades were also known as “smashers” because of the strength and velocity with which their projectiles hit their targets, causing a great splintering of wood of the ship. The wood splinters would cause the most injuries and fatalities during a ship battle.

The beaches from Point Adams and south down the coast were constantly searched. It was at this time that word came from local tribes that a portion of a ship’s hull had washed up twenty to thirty miles south of Point Adams. Upon hearing this news, Lt. Howison quickly dispatched Midshipman Simes to investigate.

What Simes found was a portion of the Shark with three carronades still sitting on top. Using a hatchet, rope, and other items, Simes was able to remove on cannon and move it to what he thought was the high-water mark. Unfortunately, the tides are tricky and when he returned with help to move the cannon he found that it was gone. No easy feat when the carronade weighs nearly one-ton!

For several decades this cannon played peek-a-boo with the residents here. In 1863 a mail carrier named John Hobson, reported seeing a cannon in Arch Cape Creek, also known as Shark Creek.

A local man by the name of James Austin became obsessed with the legend of the cannon. He was certain that he would find it and spent a great deal of money and time looking for it. Austin established the first post office at Arch Cape in May 29, 1891, calling it “Cannon Beach” after the legendary cannon. Austin never found the cannon during his lifetime; sadly, he passed away in 1894 having named the area we now know as Arch Cape – Cannon Beach.

Just a few years after Austin’s death, another mail carrier named George Luce spotted the cannon in the waters of Arch Cape Creek. He quickly notified Austin’s wife. Neighbors John and Mary Gerritse lent their team of horses to pull the heavy item out of the water. It was 1898, when the cannon was found for the last time. It was put on display in front of the post office in honor of James Austin. There the cannon sat for decades before being moved in the 1940’s to the east side of the highway.

In the 1980’s the cannon was being vandalized and was moved to the Heritage Museum in Astoria, until 2005 when the cannon was permanently loaned to the Cannon Beach History Center & Museum. It was officially given to the museum in 2017!

Weren’t there other cannons from the Shark?

Yes! In 2008, one hundred years after the first cannon was discovered. Two more were found on the beach here in Arch Cape. Those two cannon or carronades were covered in natural concretions, so they must have weighed quite a bit. It’s amazing to think that a little girl realized what the cannon was, it looked like a big rock. Officials were notified and soon a group of citizens had gathered. The removal of the artifacts was managed by Oregon State. The second cannon was found just a few days after the first. There was a lot of conversation about what would happen to the artifacts, but it’s my understanding that the U.S. Navy had some to say about these two guns. Both were sent to Texas A&M University. Texas A&M is leading in the world in maritime archaeology. The artifacts had to have the concretions removed and then analyzed. They had to know if these two carronades actually came from the Shark. After all, thousands of ships have wrecked at the mouth of the Columbia River. After both carronades had been cleaned, a British Broad Arrow was noticed on one of them. This was good news because Britain had a very detailed record of cannons made in their country. In a report from Texas A&M, “The British gun, was fortunate to have a serial number and maker’s mark, which gave us a general time and place of the gun’s casting. In this case, the maker was a small London-based firm called Wiggin & Graham, who worked as distributors to the Board of Ordinance. The gun was case in the autumn of 1805.” They knew what year and even what time of the year the cannon was made! It was even older than the Shark!

The report goes on to say, “the second gun is an American-made gun, which is again, an 18-pounder carronade.” Texas A&M believes that the American gun found in 2008 is the very same style of gun that is currently on display at the Cannon Beach History Center & Museum. In 2011, a graduate student from Texas A&M came to the museum to do an analysis of the cannon on display there and became very concerned about the shape it was in. After sitting out in the coastal weather, this iron artifact was succumbing to oxidization. To think that it survived the tsunami of ’64, the floods of ’67 and even the record breaking storms of the 1930’s, but rust was going to be its demise. After a long fundraising process, the cannon was shipped off to Texas A&M. The cannon spent nearly two years there undergoing a similar conservation process as the two cannons found in 2008.

First was a reverse electrolysis bath in a steel vat. This process went on over just over 12-months. Then there was a few boiling rinses, then a chemical treatment with a tannic acid wash. This treatment also brought back some of the dark iron luster. The artifact was also cleaned with dental tools, can you imagine? The final step was a coating of microcrystalline wax. The artifact was dipped in a boiling wax, over and over again, for an extended period of time. This sealant is mean to keep out moisture and ensure that the cannon is here for perpetuity.

The cannon that Cannon Beach is named for is currently on display at the Cannon Beach History Center & Museum in a humidity, temperature and UV light controlled case. The capstan, also known as an anchor mount, is also on display. While the museum is currently still closed, you can learn more about the history of Cannon Beach here or on the museum’s social media pages.

And as always, with love,

Your resident nerd.