The Tsunami that Changed Cannon Beach

With the recent article in the New Yorker making the rounds, I thought this would be a good time to look back on what happened in 1964. Some of you are probably saying, “Okay, I get it, tsunamis. The coast is a dangerous place.” Insert eye roll here, but the thing is a tsunami is a real possibility. And for some of us a constant threat in the back of our mind. Could what happen in 1964 be worse? Could Cannon Beach handle it?

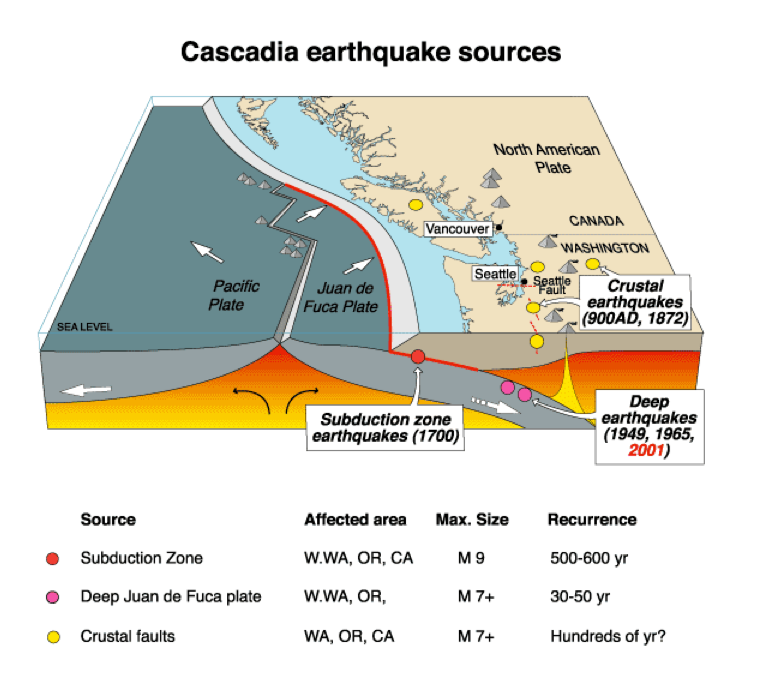

On March 27th, 1964 a Megathrust quake (sometimes referred to as the Good Friday Earthquake) shook Anchorage, Alaska to its core. The term Megathrust refers to a quake that occurs when one tectonic plate is forced under another, otherwise known as subduction. This type of quake can exceed 9.0 in magnitude; the Good Friday Quake was a 9.2. Tremors lasted for four minutes and set into motion a tsunami that swept along the North American shoreline.

Many coastal communities were unaware of the strength of such a quake, or of the tsunami heading their way.

In the early morning hours of March 27th a group of six poker players had gathered at Frank Hammond’s house. A “big bet” of fifteen dollars was on the table when the phone rang. Bill Steidel, one of the poker players, recalls, “The phone rang and one of the men got up and answered the phone. ‘They said there’s a tidal wave coming,’ he said. We all ignored it, because we heard that every winter, that there were some big waves coming. It wasn’t unusual to hear that.”

Then the second call came. The wave had hit. As Steidel recalls in his 1995 Cannon Beach History Center oral history interview, “We said (to Hammond), ‘Where are you going?’ He (Hammond) says, ‘the last wave broke over, you know that tree in my driveway – the last wave broke over the top of that tree.’”

The tree was 30 feet tall.

Steidel describes the scene as a “Laurel and Hardy picture”. Every man ran for the door at the same time. Then they scrambled into their cars and made for their families as quickly as they could.

The news of the quake in Alaska and tales of an approaching tsunami was rebuffed by some, at least at first. The community of Cannon Beach was prepared for any number of Northern squalls, floods, and fires, but this was something different, something unexpected.

Bridget Snow and her husband had a unique view from one of the bluffs in Cannon Beach. As they scanned the sea they noticed the wave approaching, “from a distance (it) moved in flat, curling to shore and rising in height about a foot a second, about ten feet in all.”

By the time the first wave made it to shore it was a thirty-foot wall of water.

Elsewhere in Cannon Beach – Margaret Sroufe glanced out her window and was shocked to see dancing blue and green orbs right before the power went out. Intrigued she made for her porch. Sroufe and her husband had an unprecedented view of the damage caused by the tsunami from their home on west side of Elm Street, “There was a house down on the creek… and there was a little duplex, and the duplex started to move… and it hit the telephone pole, and went around the telephone pole, and it ended way back up in the pasture. And the bridge lifted up and moved on back into the pasture. It came right up to the edge of our driveway. We just stood there with our arms around each other… watching the water come up.”

Those who were heading for high ground via the Ecola Creek Bridge were shocked to find that it was gone. Steidel was the first to arrive, “the bridge was gone,” he said, “The water was all around me, and then a house went by. The house went over into the meadow and settled down.”

The tsunami only picked up speed as it moved further down the coastline. In Crescent City, California it moved with such strength and velocity that when hitting the shore Seagulls were caught in mid-air by the rushing 30 foot-or more waves. Witnesses have referred to these waves as “walls of water”.

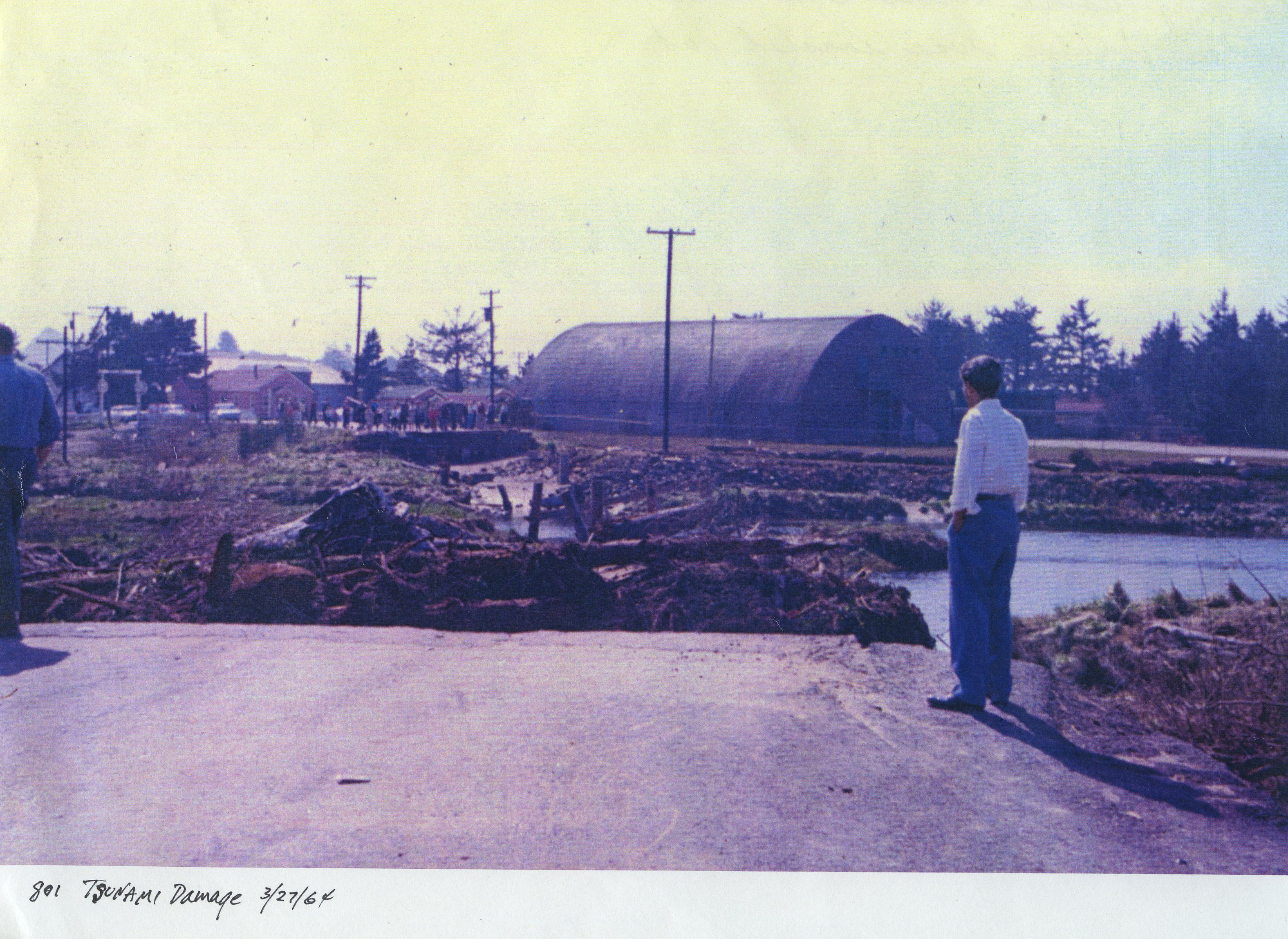

The North end of Cannon Beach was the hardest hit by the ’64 Tsunami. Homes were torn from their foundations or flooded. In addition, the Ecola Creek Bridge was completely destroyed leaving behind only skeletal pieces of wood hanging from the road on either side. Tsunami debris was distributed throughout the town. Though Cannon Beach did not experience the fatalities or devastation of other coastal communities, it was a shocking occurrence that changed how those who live at the coast react to a tsunami.

The 1964 tsunami wasn’t the first, nor will it be the last time that the coast is hit by a tsunami. The threat of a tsunami has always been a threat. There is extensive archaeological evidence and geological records that indicate past severe seismic events that have caused devastation along the entire west coast. Native American oral traditions of the region further confirm that such events have impacted ancient populations in the past. Archaeological work done in areas around Port Townsend, various parts of Oregon and northern California have shown that the Cascadia subduction zone has been and will be responsible for earthquakes and tsunamis. One such event occurred on January 26, 1700. How can we be so accurate on this date? The tsunami of 1700 was so devastating that it reached the shore of Japan and the time and date were recorded there. In addition to the records in Japan, dendrochronology and Native American oral traditions further substantiate a devastating tsunami in 1700.

Nearly every-year new information becomes available to the public thanks to the hard work of geologists, archaeologists, and other scientists. This information does not fall on deaf ears, which is why tsunami safety and preparedness has become synonymous with the Oregon coast, specifically Cannon Beach.

Cannon Beach has had a strong emergency preparedness program for years. In fact, on April 14, 2010, the New York Times commended Cannon Beach for the city’s tsunami preparedness plans. The town has been recognized for being at the forefront with their policies. Despite some of the claims in the infamous New Yorker article, many hotels in the area have evacuation plans outlined for guests, signs throughout town direct inhabitants to the safety of high ground, and local businesses have begun to construct tsunami and earthquake safe buildings. The best part is, the City of Cannon Beach, the Cannon Beach Fire Department, and the Police Station are willing to change and adopt new policies as new information becomes available or as new concerns arise. Suffice to say, the town of Cannon Beach does not use the “let’s just put that off” policy when it comes to being prepared for a natural disaster.

Education is still the number one combatant against casualties related to tsunamis and earthquakes. Safety drills, workshops, and community forums have led to a well-educated community. If you would like to know more about the tsunami that occurred in 1964, or even about the one that occurred on January 26, 1700, then stop by the Museum. We’re open 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. everyday except Tuesday.